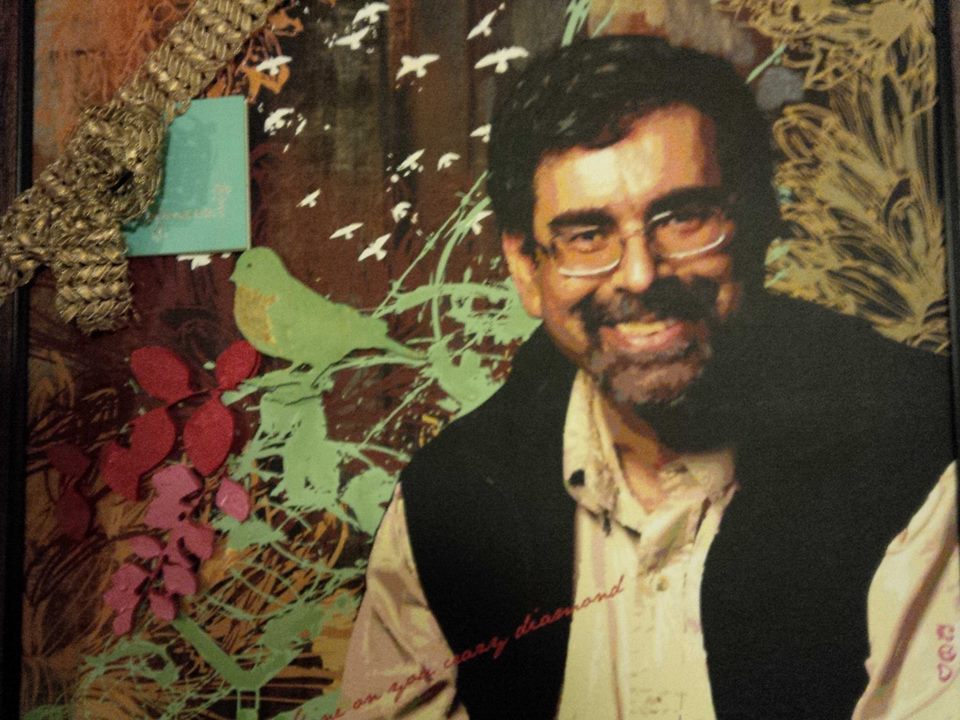

Just this month, my brother Atul Chitnis died – painfully. When that happened, I thought I would never live it down. Today, a couple of weekends after his struggle ended in death, I have time to reflect on this and I’m not sure whether to be proud of or be disgusted with myself.

You know, it’s funny – we can get over the death of a family member. I’m not sure how this uncanny ability stacks up in terms of moral brownie points, or how our illusions of family solidarity manage it. But we can do it.

There was a time in my life when I was trained to observe my own thoughts and feelings mercilessly. Delusion and self-deception were no options at all – my job was to acknowledge my emotions, accept responsibility for them, and deal with them in some way.

Back then, there were good reasons having to undergo such emotional survival drills, and I am – even today – thankful for what I learned. However, this training has the depressing quality of surfacing at the most inconvenient times. Whenever I think I have successfully rationalized myself out of a psychological tight spot, I land up in the dock once more.

Because I was unable to distract myself with work, tax problems and housekeeping today, I was forced to admit certain inconsistencies in my psyche – my brother, Atul Chitnis, was more to me than flesh and blood. I cannot escape the fact that I am trying desperately to forget he ever walked this Earth.

- I tell myself that he had the option of taking better care of himself, and didn’t.

- I tell myself that he was too demanding, requiring of me qualities that I do not have but SHOULD have had because I come from a bloodline of high achievement.

- I tell myself that there is no burden of continued grieving one me because I did a LOT of grieving after his death, and at his memorial service.

- I tell myself that I did what I could to keep him among us, but the end result was not in my hands.

- I tell myself that the living cannot and must not suffer on the account of those who died. Life must go on, I tell myself. In fact, all around me I see death denials – death is something that happens to others and not to us.

- I tell myself that he is in a better place, with no evidence at all of such a place existing in the first place.

Really?

Atul Chitnis was a man who dismissed everything but proven facts. I – not because I am his brother, but because I think this is a good premise – accept this as valid. On the basis of this premise, I have absolutely no assurance that Atul continues to exist on some ethereal plane. There are very good chances that he is gone for good.

The questions I ask myself today are:

- Did I respect him enough for being what he was – as my brother, and an acknowledged thought leader in his chosen field – while he drew physical breath?

- Did I allow my personal issues to interfere with my family loyalty?

- Did I think it was too expensive to visit him as much as he wanted me to?

- Could I (and can I now) accept and love him for what he was?

Today, when my mind has nothing else to distract itself with, the answers it produces for these questions do not flatter me at all. Today, I mourn for my brother because he was my brother, not because we did not meet each others’ expectations. Today, I am torn because I could have been a better brother to him….