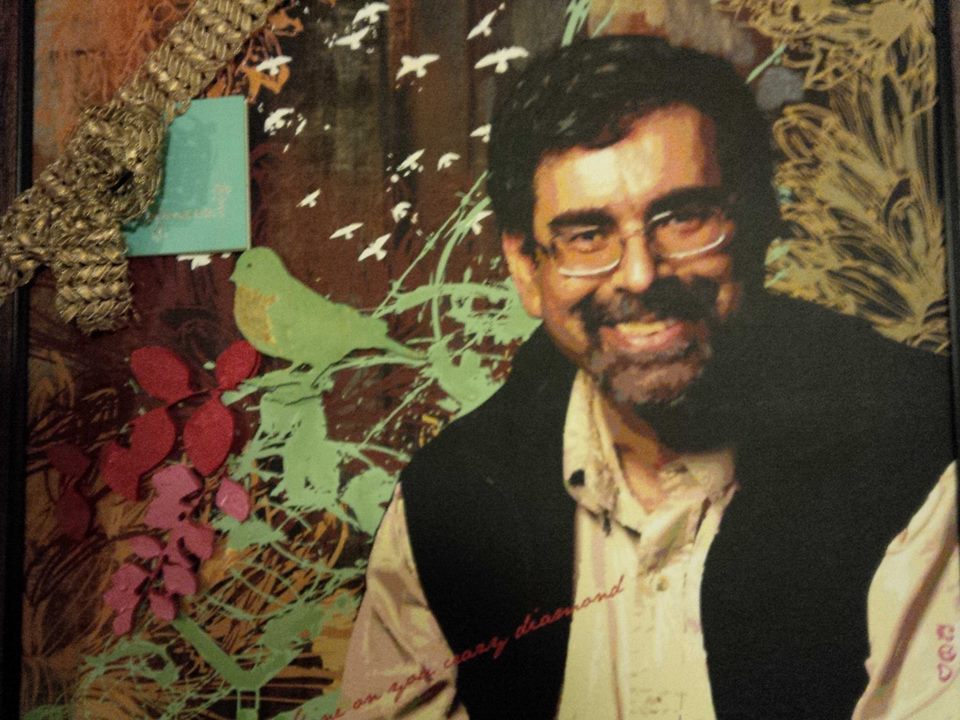

Atul’s death on June 3 sparked off a whole spate of eulogies. I knew that he was an authority on Open Source, of course – that fact was hard to escape if one spent any amount of time around him. But I must admit that I was unaware of just how much he had achieved till I read these articles.

Atul’s death on June 3 sparked off a whole spate of eulogies. I knew that he was an authority on Open Source, of course – that fact was hard to escape if one spent any amount of time around him. But I must admit that I was unaware of just how much he had achieved till I read these articles.

I was always immensely proud of Atul while he was alive, and even more now that my awareness gaps have been filled. He was the rock star of our family, and by that I don’t mean his considerable musical skills. He was the guy who made a difference, touched more lives and – despite his tendency to lay waste to anyone who did not see eye to eye with him – had more friends than anyone else in the Chitnis clan.

It has been pointed out that Atul had certain overwhelming aspects to his personality. In the articles I read, this fact was highlighted in context with his strong opinions about technology and the people who make it happen. It is true – Atul was far from subtle. In fact, he was a rampaging bulldozer on the highway of his life, and not just professionally.

I agree with the person who wrote that he had no time for mediocrity. As many of us learned the hard way, that is not always a good thing – especially when it percolates down into personal relationships. However, the part of me that I had in common with him (which is a pretty big part) has always understood where he came from. Though we followed very different paths in our adult lives, that’s where I come from too. And, apart from some other things, that’s the side of Atul and his life that I want to write about.

I may be forgiven for not writing about his technological accomplishments. Though I’m his brother, I’m nobody’s technology expert. Also, I’m a die-hard Blackberry fan and still use Windows. When I bought an iPad a couple of years ago, he was ecstatic for a while. He was under the impression that it was only a matter of time till an iPhone replaced my BB and a Mac ousted my mid-range Lenovo.

That never happened, but that does not mean that Atul did not make a ‘techie’ difference in my life. It was he who taught me how to use a computer and the Internet – the first email and chat exchanges I ever did were with him. And he practically manhandled me into buying my first mobile phone. We got along somehow, as brothers often tend to do…

Some Background….

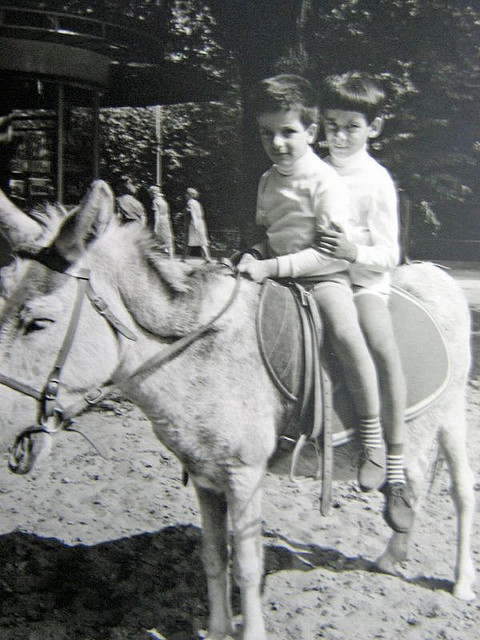

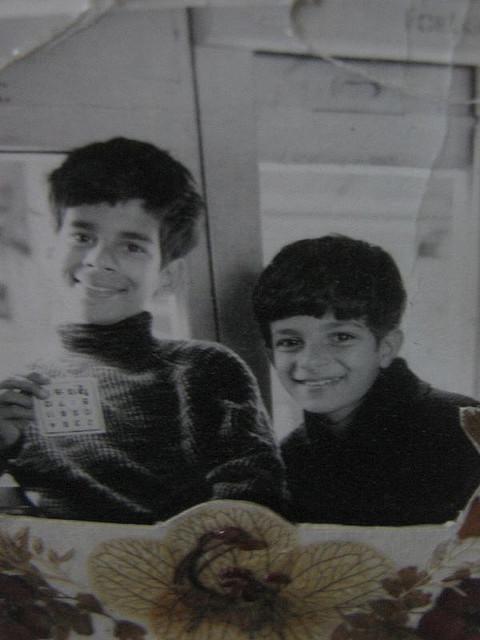

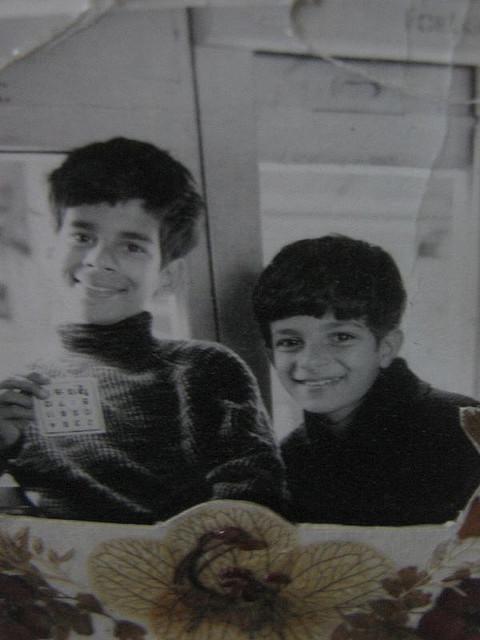

We – our mother, Atul and I – arrived from Germany in 1972. On Atul’s 10th birthday, in fact, and one month after my eighth. The only time we ever visited the country of our birth together again was in 2008 to spend Christmas with our mother.

We have been asked innumerable times why, since we were both born there, we didn’t just stay in Germany. Even though our father was an Indian, our mother is German and we had every right to. Why would anyone give up such an advantage?

I have heard Atul respond to this question in different ways, depending on who was asking. This may be hard to believe for many who knew him, but he could be diplomatic when he wanted to be. I don’t live my life in the public eye and Atul is gone, so I don’t have anything to lose by telling the truth – we had no choice. Our father had masterminded our lives long before we were done with crapping our diapers, and staying in Germany after a designated period was not part of his plan for us.

This brings me to what I consider the crux of what I’m trying to convey here.

Like it or not, sons live their adult lives in a manner which is directly or indirectly dictated by their fathers. We may either spend our entire life complying with our father’s wishes or rebelling against them. We may either do exactly what the old man taught us to do, or do exactly the opposite. But either way, the fathers of sons hold the reins from beyond the grave.

There are ways to get around this problem, but it involves shrinks and counselors and takes quite a bit of time and dedication towards personal healing. Some men invest in these methods, others don’t. Atul didn’t.

Throughout the Indian part our childhood, our father was a person to be feared and steered clear of. He was a hard and peculiar man – brilliant in his own way, but driven by his own demons and completely oblivious of how his ways affected others. He was the son of a farmer who made good – worked his way out of a dead-end Maharashtrian village, studied engineering in England and specialized in oil hydraulics in Germany.

He met our mother in London, married her, brought her back to Germany at some point and later took off to India, where he built a sizable industrial empire. We saw him only sporadically in the first few years of our lives. His empire eventually collapsed, but at the time he sent his summons for our mother and the two us to leave Germany and come to India, it was just being built. There was no question of refusing – when our father wanted something, it would happen (sounds familiar?)

And so, on February 20, 1972, we arrived at Mumbai airport. It is hard to describe how massive the contrast was, and the incredible culture shock. Two days earlier, we had left the orderly life, clean streets and neatly working systems of Berlin behind and were now confronted with the bewildering, chaotic sights, sounds and smells of what was and still arguably is India’s filthiest and most insane city. We had never seen so many people occupying so little space. Our mother had been in India a few times before, so she was better prepared.

The cacophony all around us seemed to indicate that some kind of monumental disaster had taken place. It had, but I understood only much later that the disaster was an ongoing one – a disaster called Mumbai. If there was one thing Atul and I shared throughout, it was our intense dislike of this strange city that has so successfully made a mockery of all that is worthwhile and dignified in life.

Belgaum – The Early Years

Thankfully, our stay in Mumbai was brief. Two days later, we left the banshee scream of this perpetually dying city behind to be greeted by the languid yawn of Belgaum – the city where we spent our childhood and teen years. Despite the evil memories of the events that happened there, I still love Belgaum – and in fact all small towns where life is still measured in months and years, not minutes and seconds.

The only thing there that was life-sized – or rather larger than life – was the all-engulfing, all-consuming figure of our father.

This was a man with an agenda. As I said, he had our lives all mapped out. Atul was to be groomed to take over the engineering side of his industries, and I for the commercial part. Anything that somehow appeared to deviate from this agenda was frowned on and eventually snuffed out. What counted were the highest possible marks in school and college. Even our friends were evaluated on the basis of their report cards.

Though we both had immense readjustment problems (we didn’t even speak English when we arrived) Atul’s school life in India appeared much smoother than mine. The real problems started when Atul joined college – that was the point where it became evident that he had no inclination for mechanical engineering at all.

There were only three things that really interested him by then – a charming girl called Shubha Deshpande, a guitar he had somehow wrenched out of our father, and a strange little device about the size of a grocer’s calculator.

To me, it was nothing more than that – a calculator. It turned out that this little piece made by Casio was a lot more than that. Atul would attach it to our mother’s tape recorder and fill one tape after the other with screeching sounds not unlike those we still hear from dot-matrix printers in Government offices. The device was somehow interfacing with the battered old Telefunken tape recorder. They were communicating with each other and producing those strange sounds – programs.

Between courting Shubha by day, playing the guitar in the evenings and this mysterious activity for hours on end at night, there wasn’t much time for college work. Atul’s deviation from his carefully course did not go down well with our father. There were loud, often violent rows – but Atul had inherited our father’s tendency to never back down.

His fights with our father are the most painful memories I have of our early years. He drifted further and further away. Finally, after his graduation, he left Belgaum and took up a job with a start-up software company in Mumbai and then gravitated towards Bangalore. I guess the rest is history – he married Shubha, continued to play the guitar and became an icon of the Open Source movement.

The one thing that he needed from the old man – his approval – was the one thing he did not get. When he finally did, it was too late. More than twelve years later, it fell on me to pass on to him a message from our father, who died a few months later: “Tell Atul that I am very proud of him.” I was at Atul’s house in Bangalore when I mentioned it to him, and I remember him blinking at me for a long, silent moment. Then he shrugged and went back to work on his Mac. The subject was never opened again.

Atul did come down to Belgaum to see our father as he lay dying in the ICU, but the old man’s mind had already been taken out by a massive stroke. I have no idea if the fact that his long-estranged eldest son was standing there at his bedside registered at all. I do hope that Atul experienced a small measure of healing in that brief time.

As for me, I was and still am immensely proud of what Atul did in his lifetime. I won’t pretend to understand the nitty-gritties of his work – I don’t. But sometimes, people mistook me for him at airports and in hotel lounges. Many people, on hearing my name, would ask me if I was related to Atul Chitnis. And I would tell them proudly that he was my brother…

I am almost done, and I guess whatever I have written here is a bit disjointed. I’m sorry about that, but my mind is still slightly unhinged by Atul’s death. Also, you may wonder what point I am trying to make here. Am I blaming our father for the unrelenting hardness that Atul was known for? To some extent, yes.

I tackled our father in a very different way – not very original, but effective. Atul met him head on – he gave him the middle finger and waited till he could take charge of his own life. He did that much sooner than I did. But he did not walk away a free man. The specter of not being good enough, for not meeting expectations, haunted both of us. When it came to our father, our childhood was defined by brutality and inhuman pressure to perform. You may feel that men should be able to outgrow that – and they do, but in their own ways. But there is ALWAYS a residual effect.

Everyone has their own heroes in life. I guess Atul’s was Steve Jobs – mine is John Rambo. And even though I know Rambo is a fictitious character, I relate to some things he said:

“Nothing is over! Nothing!! You just don’t turn it off!”.

No, you can’t turn it off. You deal with it – in whatever way is available to you, whatever way you know, or it will poison the rest of your life.

“Live for nothing – or die for something!”

Atul lived for Open Source. He may not have died for it, but he lived for it. Please remember him that way, even if you forget everything else about him.

As I mentioned, it takes informed guidance and personal dedication to healing from such wounds if one is to overcome them. Atul had no time or patience for such stuff. He had better things to do – and one of the reasons why so much has been written about him is that he was pretty damned good at what he did.

The End

Watching Atul suffer was horrible. He knew what was coming, but he refused to accept that all possible medical avenues had been explored – and that somehow contributed to his suffering. This was a man who loved life, but had not taken the necessary steps to safeguard it. Everything that was attempted after the diagnosis of stage 4 colonorectal cancer was basically futile damage control – locking the stable after the horse had run away.

There were only two times in my entire life when I had the balls to tell him that I love him. The first time was just after the diagnosis, and I said it in the fleeting, offhand way that men tend to use when they are expressing deep sentiments. The second and last time was when he was unconscious in his own ICU bed, breathing artificially through a respirator – a couple of hours before he died. I don’t know whether he heard me.

Somehow, I hope he didn’t, if you can dig it. But I want to say it once more – and I figure that if any part of Atul is still around, it just HAS to be online.

I love you, bro. I thank God that your suffering is over and curse Him for taking you in the first place. I miss you so very, very much…

I love you, bro. I thank God that your suffering is over and curse Him for taking you in the first place. I miss you so very, very much…